John Snow, M.D.: Early Career

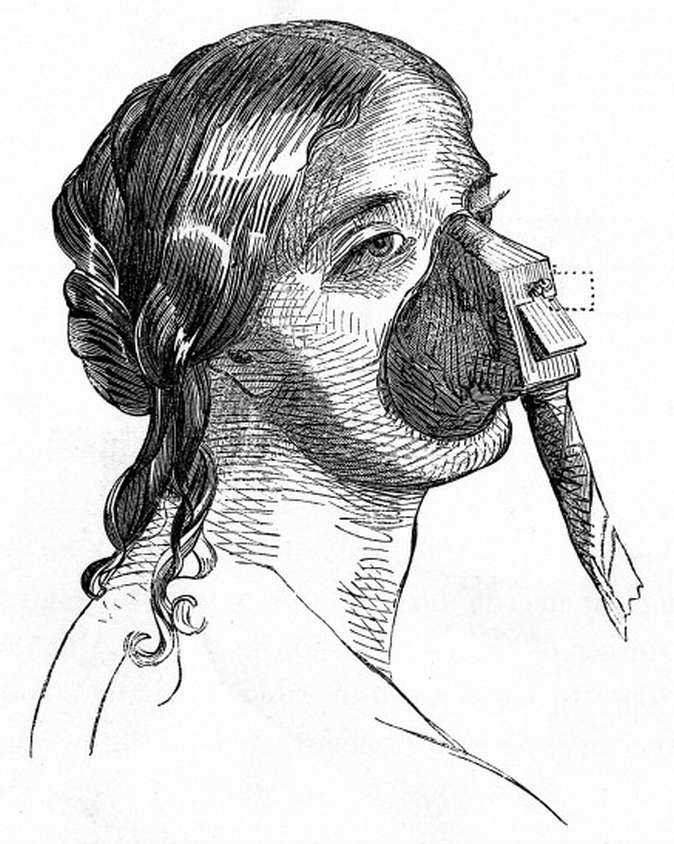

John Snow: "Autotype from a presentation portrait, 1856,

and autograph facsimile." Credit for both image and caption, Wellcome

Library, London.

Little wonder that John Snow (1813-1858), the doctor who

discovered how cholera was transmitted and thrust his findings in the

face of a disbelieving medical establishment, should have become one of

the heroes of medical science. A farmer's son from the north, who

trekked all the way to the great metropolis to (eventually) become its

saviour, his story is the very stuff of legend. Even by today's more

measured assessment, he remains a towering figure, especially in the

fields of epidemiology and public health.

Born in York, John Snow was the son of a Yorkshire labourer who later

became a relatively well-to-do farmer. The youth was apprenticed at

fourteen to an enlightened and well-connected Newcastle surgeon, William

Hardcastle, who was on the staff of Newcastle's Lying-In Hospital.

He first came up against cholera when it swept through the nearby West

Moor colliery, a few miles from town by the village of Killingworth.

This was during the epidemic of 1831-32. But at the time when cholera

broke out again in 1846 Snow was in London. Having travelled to London

on foot in 1836, Snow had now completed not just his apprenticeship but a

thorough all-round training, including surgical practice at Westminster

Hospital. In 1838 he had moved to Soho, opening a practice in Frith

Street there, and also attending out-patients at Charing Cross Hospital,

only a short distance away. He had subsequently earned medical degrees

at the University of London (now University College, London), which had its medical facilities at University College Hospital.

In 1845 he had become a lecturer in forensic medicine at the

short-lived Aldersgate School of Medicine — though a large part of his

experience had been in obstetrics, and his early interest was in the

resuscitation of still-born infants, he also had a specialised knowledge

of lead poisoning. Besides, in whatever he had undertaken, he had

proved himself a keen and cutting-edge investigator. By the late 1840s

he was best known for his research into anaesthesia, having published a

groundbreaking study, On the Inhalation of the Vapour of Ether in Surgical Operations, in 1848.Dr Snow's Early Investigations into Cholera

Snow had been a high-minded young man, a vegetarian as

well as a teetotaller. In his more mature years, he was still a man of

integrity, evincing "a complete lack of acquisitiveness and personal

ambition" (Hempel 106). A bachelor, he was wedded to his work, endlessly

painstaking in it, and dedicated to his scientific and humanitarian

pursuits. On the theoretical level, he had approached the subject of

anaesthetics from many different angles, from looking at the properties

of the gas itself to studying its physiological and psychological

effects. He had followed his findings right through to the practical

stage as well, working out and designing the best means of

administration. He had tested his inhalers in animal experiments, and

had not shrunk from testing them on himself (see Johnson 65-68). Armed

with his understanding of the operation of gases, when he again found

himself treating cholera cases in his neighbourhood, he was not inclined

simply to accept the prevailing "miasmic" orthodoxy.

Moreover, he was prepared to follow unusual routes to establish his own

theory. These ranged from reading accounts of the previous epidemic and

examining current cases to consulting chemists, water suppliers and

sewer authorities (see Johnson 71-74). By these means he worked out to

his own satisfaction that the disease was spread not by touch, not

through the air, but by ingestion. As he himself put it: "The morbid

material producing cholera must be introduced into the alimentary canal —

must in fact be swallowed accidentally, for persons would not take it

intentionally" (Snow, On the Mode of Communication, 15).

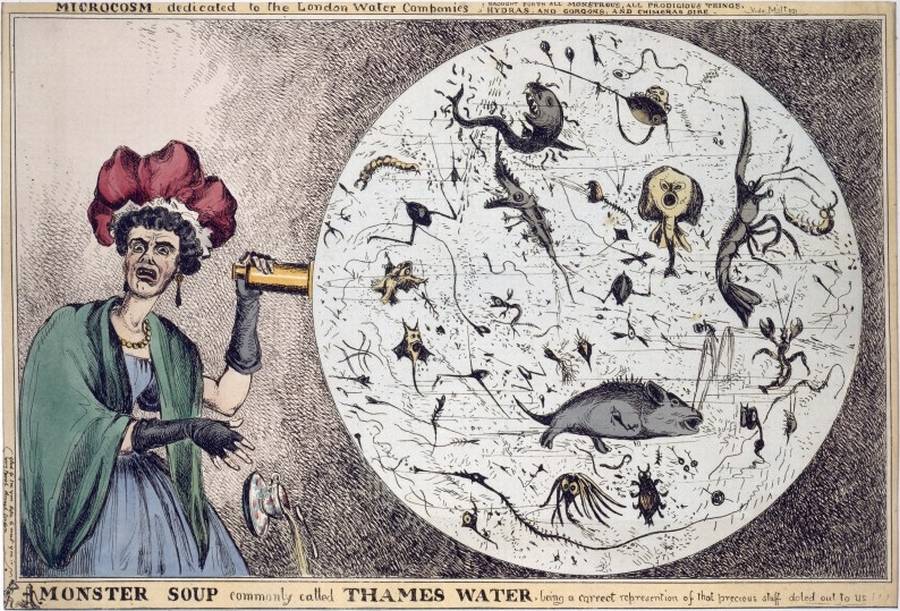

Left: "Monster Soup, being a correct representation of

that precious stuff doled out to us." A coloured etching by William

Heath (1795-1840), 1828. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Microscopic

demonstrations had become popular at this time, but a woman drops her

cup of tea in horror when she realises what Thames water might contain.

Ironically for the present subject, a tiny figure in the left-hand

corner doffs his hat to a water pump, supposedly a source of cleaner

water. Right: A Punch illustration, in an article of 1850

entitled "The Water Kings," shows a boy shrinking away from the glass of

water offered by Old Father Thames, who has his other hand on a tap

(Vol. 18, p.62).

In an overcrowded city, with only the most primitive provisions for

disposing of human waste, the finger pointed at contaminated water. In

1849 Snow published what should have been another groundbreaking paper, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera,

demonstrating that more people died from cholera in the area served by

certain South London water companies. These drew their water straight

from the River Thames, which, at this time, had around sixty sewage

outlets gushing into it (White 51).The Reception of Dr Snow's Theory

Everyone knew the disgusting state of the Thames.

Chadwick's insistence on removing human waste from cellars, and running

it into the current drainage system, had only made it worse, as had the

growing popularity of water closets. However, Snow's paper failed to

make as much impression as the smell of the river itself. Another

doctor, who still favoured the widely-held miasmic theory of

contaminated air, wrote in the same year,

That cholera is produced by a specific poison is generally

admitted by writers upon the subject. As to the essential nature of

this specific miasm we are entirely ignorant; and we do not think it

would serve any useful purpose to enter into a discussion upon the

various hypotheses which have been proposed. For the most part the

explanation offered to account for the mode of action of any one miasm

will not cover the whole question; and this, in our opinion, is a fatal

objection, for it is obvious that they present but one problem; and the

true solution, when it comes, will explain all the varieties of the

phenomenon. (Russell 122)

Others discussed Snow's hypothesis but mistrusted it: "At

present these opinions of Dr Snow's can be considered only ingenious

speculation," said one (Bushnan 33).

The Broad Street Pump

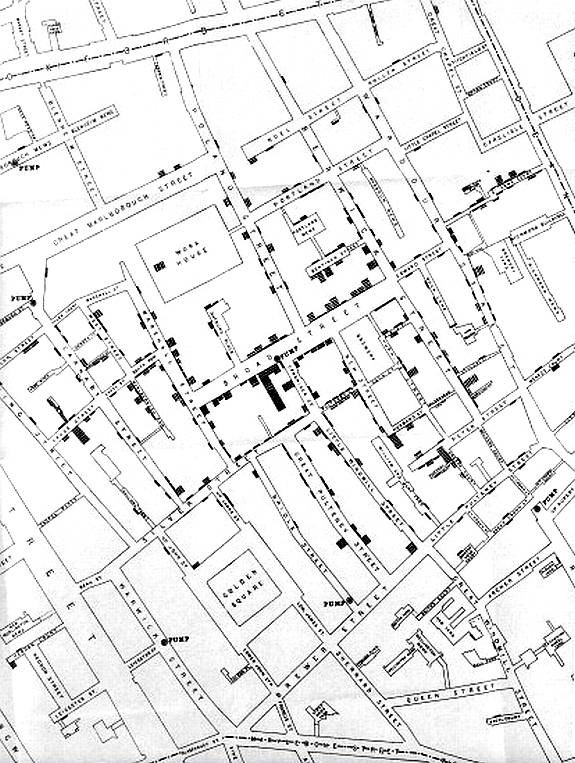

Left to right: (a) John Snow's house in Sackville Street,

off Piccadilly (since demolished), with a plaque describing him as

"physician and specialist anaesthetist who discovered that cholera is

water-borne." (b) Snow's map of the area that provided the best evidence

for his theory, around the Broad Street pump. Broad (now Broadwick)

Street, W1, is the street that runs diagonally across the middle. Here,

the black bars merge to denote houses where people died of the disease.

These stand alongside the pump on the corner with Cambridge Street (now

Lexington Street). (c) Silhouette of the pump indicating its original

location. A replica has now been placed nearby. Credit for all three

images: Wellcome Library, London.

Snow, who was nothing if not tenacious, now set out to

provide precise evidence in support of his theory. This time, supported

by another local doctor and vestryman Edwin Lankester, and at

street-level by local clergyman Henry Whitehead, he focused his

investigation on the Broad Street area of Soho. Using statistics

acquired from the General Register Office, he was able to demonstrate

graphically that an unusual number of the 1853-54 fatalities had

occurred among those drinking water from the pump there. The map on

which he charted these fatalities was not the first to highlight

clusters of a disease. But, after showing it to the Epidemiological

Society in December 1854, he made a significant modification. Around the

black bars representing the houses where deaths had occurred, he drew a

line indicating closeness by foot to the pump. The uneven line,

following the street pattern, made it clear that this was not a case of

simply breathing in the air around the pump. He was also able to

demonstrate that those who lived nearby, but drank from different

sources (such as the local brewery's pipeline), had been spared.

Finally, Whitehead did him a signal service by helping uncover the

original source of the contamination: from talking to a bereft mother,

he learnt that contaminated water had been thrown into a nearby

cesspool. This proved to have leaked its virulent contents into the

water source. As Lankester would say later, "the evidence adduced [in

the revised monograph pf 1855] was most circumstantial and conclusive" . Though the epidemic was dying out by then, the parish Board of

Guardians agreed to remove the pump handle so that people could no

longer use it.

Reception of the Revised Edition of Dr Snow's Monograph

Snow seemed to have presented an open and shut case for

his theory that the dreaded disease was passed on, as he was now able to

formulate it, by the mixture of cholera evacuations with the water used

for drinking and culinary purposes, either by permeating the ground, or

getting into wells, or by running along channels and sewers into the

rivers from which entire towns are sometimes supplied with water.

Whitehead had certainly been convinced, Lankester perhaps

less so at that time. But at any rate the Board of Guardians had acted

on Snow's findings. In the eyes of the medical establishment, however,

the jury was still out. "This mode of conveyance was so novel that when

first suggested it was almost universally opposed," said Lankester,

adding "not a member of his own profession, not an individual in the

parish believed that Dr Snow was right" (30-31; 34-35). Opponents of

the theory continued to insist that there were other outbreaks that it

failed to cover. They still preferred to blame "the atmosphere or its

concomitant imponderable agents" (Acland 77). The Lancet

criticised Snow savagely in its issue of 26 June 1858: "The fact is,

that the well whence Dr Snow draws all sanitary truth is the main sewer.

His secus, or den, is a drain" (qtd. in Johnson 205). Even in

1861, Mrs Beeton's specifics against cholera were "cleanliness,

sobriety and judicious ventilation" (1073), not clean drinking water.

Florence Nightingale, who nursed so many cases of the disease in the

Crimea, remained a "convinced miasmatist" all her long life.

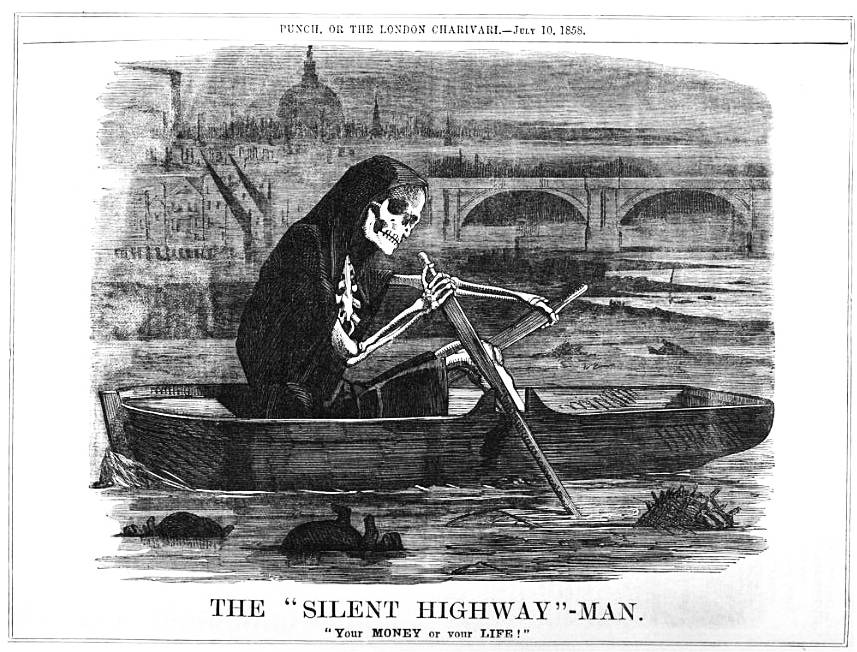

John Tenniel's famous cartoon, in the Punch

of 10 June 1858 (facing p.17), shows a skeleton rowing along the

Thames, with dead creatures floating alongside, and St Paul's, beloved

symbol of the city and its spiritual life, in the distance. The Thames

was still "a river of death" at this time, and the remedy involved a

heavy financial commitment — hence the sub-caption, "Your MONEY or your

LIFE!"

However, once he was thoroughly convinced, Lankester became a

formidable ally to the cause. Appointed the first medical officer of

health for Westminster in 1856, he was "a born publicist, teacher and

reformer" (English). When The Lancet finally

came round in 1866, it heaped praise on Snow as a "great public

benefactor" who had "enabled us to meet and combat the disease" (qtd. in

Johnson 213). At this time too, the last outbreak of cholera convinced

William Farr, the superintendent of statistics at the General Register

Office, that Snow had been right, and that water was, if not the only,

then at least the most important, vehicle of the infection: he found

that almost all those recently affected were getting their water from a

part of the river not yet properly served by Joseph (later Sir Joseph) Bazalgette's

new sewerage system. Though Farr never quite gave up his own belief

that environmental factors were involved as well (see Eyler 230), this

allowed social science to align itself more securely with Snow's

detective work.The Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini had already discovered the agent that caused cholera by then. When Robert Koch isolated it in 1883, and gained publicity for his findings, the last piece of the puzzle fell into place. Vibrio cholerae thrives in an aquatic environment — and inside human intestines. The accuracy of Snow's finding, and its full implications, could now be properly appreciated.

Dr Snow's Death and Reputation

Left: Equipment for the use of ether as an anaesthetic.

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Snow's pioneering work in this area

was more widely recognised in his own lifetime. Right: Snow's grave in

Brompton Cemetery,

with a replica headstone replacing the one that was destroyed in an

air-raid during the last World War (photograph by the present author).

In his final decade, Snow achieved eminence as an anaesthetist, attending Queen Victoria

in her last two childbirths, in 1853 and 1857. On the first occasion,

he and his colleagues had been criticised in the ever-sceptical Lancet

(see "Anesthesia and the Queen"), but by the second, the queen's own

endorsement had made the practice acceptable. However, Snow had a stroke

in the following year, while preparing his latest work, On Chloroform and Other Anaesthetics

(1858), for publication. He was found to have had underlying health

problems, which his experiments on himself, not to mention the

opposition to his ideas about cholera, might well have exacerbated.

Nevertheless, John Snow is still a very important figure in the history of epidemiology. The Broad Street episode is seen, appropriately enough, as a "watershed event," significant not simply because it proved Edwin Chadwick and the many other miasmatists to be wrong, but also because it showed that an epidemic could be tackled by practical intervention. It marks "the first time in history when a reasonable person might have surveyed the state of urban life and come to the conclusion that cities would someday become great conquerors of disease" (Johnson 235). The fact that hardly any "reasonable person" did appreciate this at the time is an important part of the story — the story of one man's doggged search for an answer, and persistence in trying to convince others that he had found it. This story has a life of its own outside the annals of medical science. Snow's greatest achievement may be in encouraging us to confront the problems that face the world today, and to have the courage of our own convictions, so that we too can help secure a viable way of life for future generations.

HOW I GOT CURED OF HERPES VIRUS.

BalasHapusHello everyone out there, i am here to give my testimony about a herbalist called Dr imoloa. i was infected with herpes simplex virus 2 in 2013, i went to many hospitals for cure but there was no solution, so i was thinking on how i can get a solution out so that my body can be okay. one day i was in the pool side browsing and thinking of where i can get a solution. i go through many website were i saw so many testimonies about dr imoloa on how he cured them. i did not believe but i decided to give him a try, i contacted him and he prepared the herpes for me which i received through DHL courier service. i took it for two weeks after then he instructed me to go for check up, after the test i was confirmed herpes negative. am so free and happy. so, if you have problem or you are infected with any disease kindly contact him on email drimolaherbalmademedicine@gmail.com. or / whatssapp --+2347081986098.

This testimony serve as an expression of my gratitude. he also have

herbal cure for, FEVER, BODY PAIN, DIARRHOEA, MOUTH ULCER, MOUTH CANCER FATIGUE, MUSCLE ACHES, LUPUS, SKIN CANCER, PENILE CANCER, BREAST CANCER, PANCREATIC CANCER, CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE, VAGINAL CANCER, CERVICAL CANCER, DISEASE, JOINT PAIN, POLIO DISEASE, PARKINSON'S DISEASE, ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE, BULIMIA DISEASE, INFLAMMATORY JOINT DISEASE CYSTIC FIBROSIS, SCHIZOPHRENIA, CORNEAL ULCER, EPILEPSY, FETAL ALCOHOL SPECTRUM, LICHEN PLANUS, COLD SORE, SHINGLES, CANCER, HEPATITIS A, B. DIABETES 1/2, HIV/AIDS, CHRONIC RESPIRATORY DISEASE, CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE, NEOPLASMS, MENTAL AND BEHAVIOURAL DISORDER, CHLAMYDIA, ZIKA VIRUS, EMPHYSEMA, TUBERCULOSIS LOW SPERM COUNT, ENZYMA, DRY COUGH, ARTHRITIS, LEUKAEMIA, LYME DISEASE, ASTHMA, IMPOTENCE, BARENESS/INFERTILITY, WEAK ERECTION, PENIS ENLARGEMENT. AND SO ON.